Dictaphone Group, Nothing to Declare, Edinburgh Fringe Festival, 16-21 August 2013.

The term “metaphor,” as an intellectual transfer between discursive planes, shares an etymological connection with “transport,” or the physical displacement of a body across space. Inherent to the two notions is an implicit expectation of transformation. To move is to be moved. To travel is, potentially, to change. Hence, the apparent banality of transportation infrastructure masks the myriad ways our lives are shaped and entangled by our ability to move. The disappearance of a train route, then, is always about more than just logistics. It is a metaphor of a changing “social contract” between citizens and the state.

Dictaphone Group is a Lebanese research and performance team that consciously blurs the boundaries between art and knowledge production. Their most recent project can be read as an elaborate extension of the above-mentioned transportation metaphor. In Bus Cemetery (2011), the group invited audiences aboard a disused bus last seen on the streets of Beirut sometime in the 1990s. Therein, the audience was taken back in time to a period before the Lebanese civil war, when public services—now seen as a burden on a state—were mobilized without the suspension of disbelief. Similarly, in This Sea is Mine (2012), the group transported audiences both physically—on a fisherman’s boat along the Beirut seashore—and metaphorically—into a mindset that shattered the apparent banality of private encroachment of public land.

From this perspective, Nothing to Declare is that same transportation metaphor taken to its logical conclusion. It is the metaphorical use of the “ruinscapes” of a public transport system, traversed to tell stories from its peripheries. At the same time, these stories bring to light what is already metaphorical and more-than-utilitarian inside the everyday banality of urban infrastructure. In Nothing to Declare, Tania El Khoury, Abir Saksouk-Sasso, and Petra Serhal trace the historical train routes through Lebanon to tell a particularly Lebanese story, or rather Lebanese stories, of leisure, borders, checkpoints, housing, and displacement along Lebanon’s train tracks. However, the subliminal message they convey is universal: travel any distance across any map and similar stories of injustice are likely to emerge.

The performance opens with a projected video showing El Khoury, Saksouk-Sasso, and Serhal in conversation, standing in the middle of a street, under the rusted remains of an elevated track now scratched with Armenian graffiti. The three women are in Mar Mikhael, the location of a former train station now housing the headquarters of the Office des Chemins de Fer et des Transports en Commun (OCFTC)—the private-public rail authority that still oversees Lebanon’s ghost train network.[1] Cars dodge the three performers as a voiceover situates the project within an atmosphere of frustration with national borders borne out of that rolling wave of commonality that swept through the region at the start of the Arab uprisings of 2011. This anchoring of Nothing to Declare within a diffuse critique of border regimes—especially those between ostensibly “fraternal” Arab states—is important to keep in mind throughout the performance, as it helps explain the kinds of stories highlighted along the way. It also foreshadows the political role the Dictaphone Group envisions for their project as a whole, as detailed in another voiceover sequence at the very end of the show.

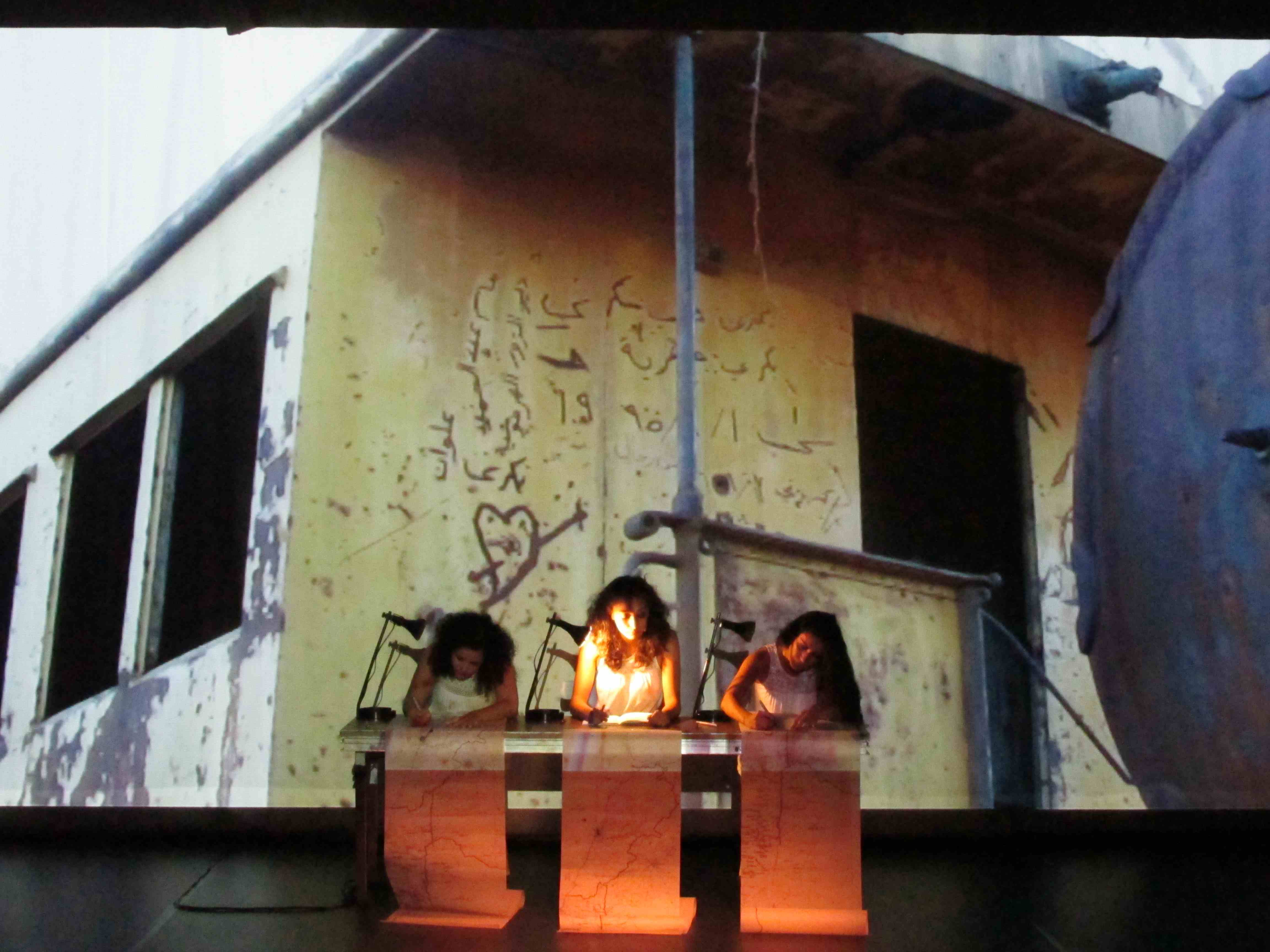

[Openning scene from Nothing to Declare. Image by Dictaphone Group]

As the three journeys begin in the projected video, we are shown El Khoury driving north, Saksouk-Sasso going south, and Serhal taking the eastern route—each following one of the train tracks and heading in the direction of her family’s town of origin. At that point in the video, the three performers step out from behind the screen to reveal themselves to the audience. They are barefoot and dressed in identical white dresses. In turn, they take a seat at a long wooden desk with three chairs, three lamps, and three notebooks. They face the audience like a panel, their backs to the projection. As the voiceover ends and the last notes of the accompanying soundtrack play, they unfurl three scrolls of paper that spill across their desks and towards the audience. Some in the audience will immediately notice that these are three identical maps of Lebanon. Others will only realize this fact as the dimly lit show progresses, watching the three hunched over, laboriously marking down and annotating their routes in between their live narrative sketches.

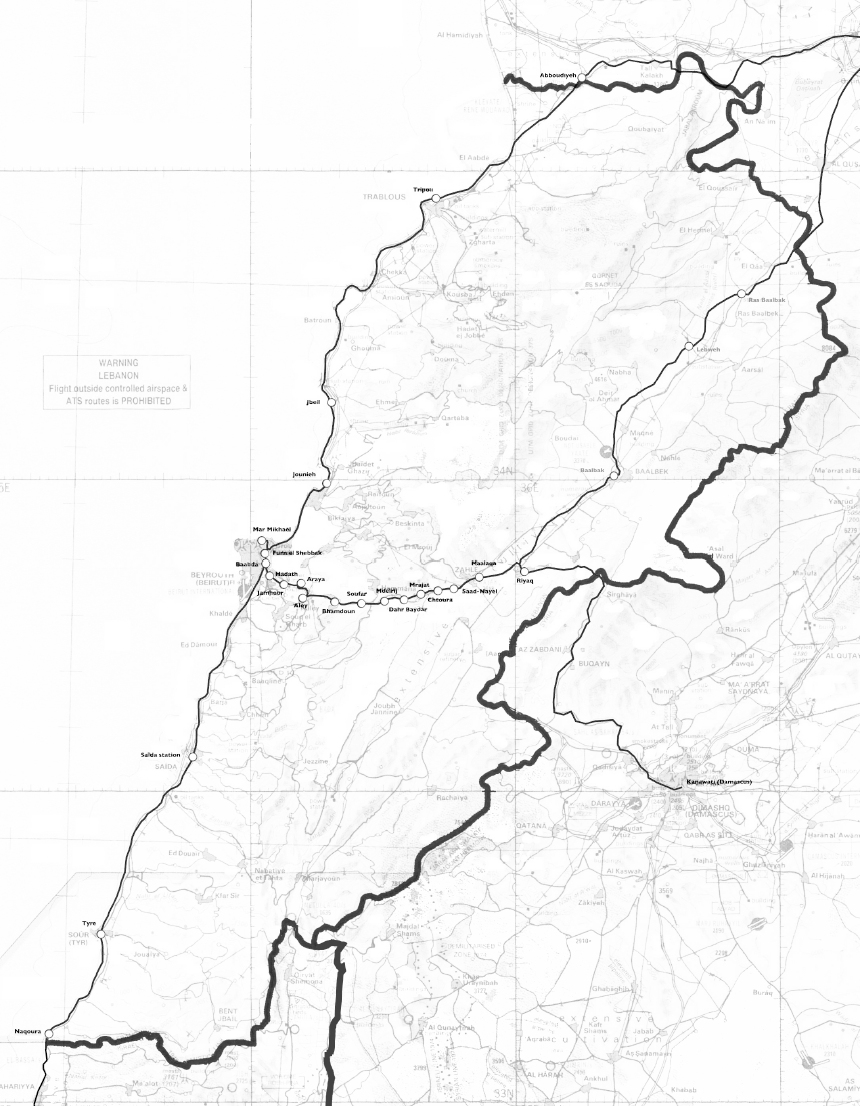

[Map of Lebanon showing the three train tracks. Circles along thin line represent stops along the route

Thick lines demarcate borders of Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria. Map by Dictaphone Group.]

For the rest of the show, a montage of video clips, live body movements, and light switches animate the oratory performance backgrounded by the video projection of the parts of Lebanon through which the trains passed. There is a subtle theatricality to this mise-en-scène. The seating arrangement evokes an atmosphere of sober deliberation, that something of great importance is taking place—as in a court or tribunal. This feeling is accentuated by the gavel-like click of the desk lamps turning on and off as the performers alternate reading out their handwritten statements. The texts weave together the personal testimonies, familial memories, historical documents, and other research findings about the tracks, the trains, their operators, state officials, and others. The group divulges what soldiers positioned in stations-turned-bases told them in confidence about the train tracks that are no longer there. At one point, they flag up a statue commemorating the Syrian-Lebanese project to reopen the northern route; a project that never happened. At another point, they accuse ex-President Elias Hrawi of “destroying” the Ma‘alaka train station “and replacing it with a hospital that carries his name.”

At times, the atmosphere of the performance borders on the ominous, conjuring images of interrogation rooms in the dark. Yet, the mood is also softened by the gentle tone of the storytelling, the performers’ choice of attire, and the way they downplay the pivotal role their personal courage and negotiation skills played in the “doing” of the research and the “making” of their narrative. Dictaphone Group navigate this somewhat uneasy middle-ground between the coldness of critical research and the intimacy of good theater with skill and humor throughout the performance. At times, the austere and no-nonsense desk lamps are transformed, with a slight gesture, into oncoming trains, as when Sasouk-Sasso tells the story of railway workers protesting a 1970 proposal “to terminate the entire railway system.” These same lamps later transform into a theatrical “editing machine,” as El Khoury and Sasouk-Sasso go back and forth, each narrating the history of one of two Palestinian refugee camps at opposite ends of the country. We are told the story of a group of refugees shuttled out of their already dismal tent city in the south, beaten and forced onto a train that took them even further from Palestine. The train was destined for Syria, but on 7 October 1948 was forced to stop in Tripoli because the authorities across the border decided to bar them entry. For ten days, the refugees stayed in the train wagons awaiting their fate. “And this is how Nahr al-Bared refugee camp started,” El Khoury ruefully informs us.

[El Khoury, Serhal, and Saksouk-Sasso during a Vienna performance

of Nothing to Declare in June 2013. Image by Dictaphone Group]

At a different point, El Khoury and Serhal toy with the expectations of theater, mock-fumbling through a reenactment of a real telephone conversation between Prime Minister Rafik al-Hariri and the head of the OCFTC, whom Serhal calls “Beshara the Brave.” This story, about how a post-war “peace train” was put out of commission, is yet another example of the brute force, sustained effort, and unaccountable overreach that went into consolidating the “Second Republic.”

Nothing to Declare is full of explosive vignettes like these. Some will be familiar to those who know Lebanese politics, or who pay attention to urban issues in the country. Others will be so shocking as to enrage, or, alternatively, elicit a chuckle at the surrealism of the story. Either way, one cannot imagine any audience member emerging from the performance wholly unsurprised or not having learned something new. For example, hearing the gripping, first-hand accounts of the men who operated the last train on each of the three train tracks, each one grinding to a halt at a particular juncture in both the geography and history of Lebanon, is enough to make the whole performance worthwhile. With their artful combination of original research, video documentation—including the use of spy and phone cameras to circumvent security restrictions—and personal testimonies, the Dictaphone Group effectively demonstrate how empirical research is never “neutral” or “purely academic.”

While the performative aspects of the piece may make citing their research findings more difficult, such an approach would miss the real power of the work. With Nothing to Declare, the Dictaphone Group successfully reinforce the notion of the control of borders, the state-provisioning of services, and the displacement of people as matters of concern. The materials they present are in and of themselves useful for opening up new avenues of inquiry into how exactly we came to the situation we find ourselves in today—as Lebanese or Arabs in general. However, there is a deeper truth they uncover, which is the very political nature of the act of inquiry. Every “dry finding” is imbued with emotion, and every “documented fact” is one link in a caravan of broken promises barreling down on us, one after the other, whether we are researchers or citizens. Nothing to Declare ends with the performers’ backs to the audience, facing projections of themselves looking out across the three Lebanese border zones: the southern border with Palestine, as well as the northern and eastern borders with Syria. We are made to understand that they have reached the limits of where their sousveillance and negotiations with power could take them. Then, Dictaphone Group reveals the true purpose of their travel. They documented three journeys in Lebanon so that they could cross the Arab world, using their art as a vehicle:

We aim to tour this project throughout the Arab world, including Palestine. In each Arab country, the performance will be expanded through site-specific oral history about people’s mobility in that particular country, and about our journey crossing the borders to get there.[2]

With Nothing to Declare, Dictaphone Group smuggle us across and then dismantle the border between art and research. This enlivens both fields of practice, and—one would hope— provides inspiration to those of us looking for another way to do politics again. As activists, it urges us to think beyond the narrow confines of “policy transfer” and “awareness building” when striving for infrastructural reform: Are we reaching out and learning from the individuals and communities that are using or holding on to the systems we want to improve? As researchers, it pushes us to take our criticality one step further: Does our work have the impact we would hope to see in the world?

Performance Intro Video

-------------------------------------

[1] Since September 2011, under the directive of Public Works and Transport Minister Ghazi Aridi, the OCFTC has also been putting a modest fleet of buses back into operation.

[2] Dictaphone Group, Newsletter (12 August 2013).